More than four years have passed since the discovery of one of the most sophisticated and dangerous malicious programs – the Stuxnet worm, considered the world’s first cyber-weapon. With many mysteries around the story, one major question revolves around what the exact goals of the whole Stuxnet operation were.

More than four years have passed since the discovery of one of the most sophisticated and dangerous malicious programs – the Stuxnet worm, considered the world’s first cyber-weapon. With many mysteries around the story, one major question revolves around what the exact goals of the whole Stuxnet operation were.

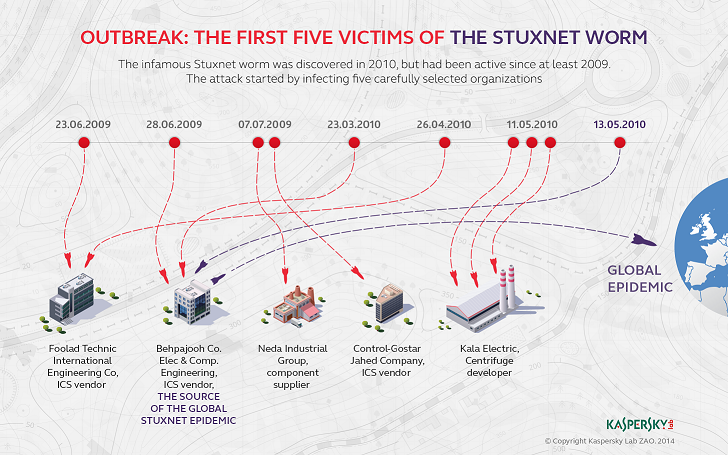

After analysing more than 2,000 Stuxnet files collected over a two–year period, Kaspersky Lab researchers can now identify the first victims of the worm.

Initially, security researchers had no doubt that the whole attack had a targeted nature. The code of the Stuxnet worm looked professional and exclusive; with evidence that extremely expensive zero-day vulnerabilities were used. However, it wasn’t yet known what kinds of organisations were attacked first and how the malware ultimately made it right through to the uranium enrichment centrifuges of top secret facilities.

This new analysis sheds light on these questions. All five of the organisations that were initially attacked operate within the Industrial Control Systems (ICS) area in Iran, developing ICS or supplying materials and parts. The fifth organisation to be targeted is the most intriguing because, among other products for industrial automation, it produces uranium enrichment centrifuges. This is precisely the kind of equipment that is believed to be the main target of Stuxnet.

It is believed the attackers expected that these organisations would exchange data with their clients – such as uranium enrichment facilities – and this would make it possible to get the malware inside these target facilities. The outcome suggests that the plan was indeed successful.

Kaspersky Lab experts made another interesting discovery, revealing that the Stuxnet worm did not only spread via infected USB memory sticks plugged into PCs. This factor shaped part of the initial theory, explaining how the malware could sneak into a place with no direct Internet connection.

However, data gathered while analysing the very first attack showed that the first worm’s sample (Stuxnet.a) was compiled just hours before it appeared on a PC in the first attacked organisation. This tight timetable makes it hard to imagine that an attacker compiled the sample, put it on a USB memory stick and delivered it to the target organisation in just a few hours. It is reasonable to assume that in this particular case, the people behind Stuxnet used other techniques instead of a USB infection.

“Analysing the professional activities of the first organisations to fall victim to Stuxnet gives us a better understanding of how the whole operation was planned. At the end of the day, this is an example of a supply-chain attack vector, where the malware is delivered to the target organisation indirectly via networks of partners that the target organisation may work with,” Alexander Gostev, Chief Security Expert at Kaspersky Lab, said.

The latest technical information about some previously unknown aspects of the Stuxnet attack can be read in a blog post on Securelist.

An infographic illustrating the timeline of the first five attacks can be seen below.

The newly released book – “Countdown to Zero Day” – by journalist Kim Zetter, also includes previously undisclosed information about Stuxnet, some of which is based on interviews with members of Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team who are helping to unravel the Stuxnet mystery.