Ultra-realistic humanoid robots are once again testing the boundaries between engineering achievement and public comfort, as new models unveiled by Chinese robotics firms generate both technical interest and social controversy.

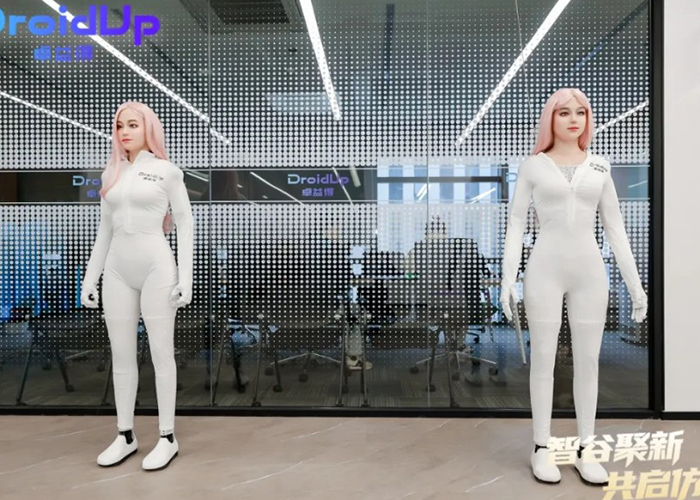

Shanghai-based robotics startup DroidUp recently introduced a humanoid platform known as Moya, described by the company as a biomimetic, embodied intelligent robot. According to official materials, the system incorporates synthetic skin, temperature regulation, facial micro-expression capability and AI-driven perception designed to enable more natural interaction in public environments.

The engineering ambition is clear: move beyond rigid, mechanical humanoids toward systems that more closely replicate human appearance and motion. The company positions the platform for service-oriented applications such as reception, customer engagement and public-facing roles where social interaction is required.

But the reaction has been mixed. While some observers see the robot as a milestone in embodied AI and human-robot interaction, others point to discomfort triggered by its near-human appearance. This reaction aligns with what robotics researchers have long described as the “uncanny valley” — the phenomenon where entities that are almost, but not quite, human can provoke unease rather than acceptance.

The controversy is not limited to a single company. Other Chinese technology firms have recently showcased humanoid robots with increasingly fluid movement and lifelike proportions. In at least one case, online speculation suggested the robot was actually a human performer in a suit due to the realism of its movement. The manufacturer responded by publicly demonstrating the robot’s mechanical structure to counter the claims, highlighting a growing challenge in the sector: credibility and trust.

From a systems perspective, the issue is less about appearance and more about capability. Ultra-realistic exteriors do not necessarily correlate with functional autonomy, decision-making reliability or operational robustness. The core technical challenges in humanoid robotics remain consistent: stable locomotion, dexterous manipulation, safe human interaction, power efficiency and real-world adaptability.

Expressive faces and lifelike gestures are being developed to improve human-robot interaction, particularly in environments such as healthcare, hospitality and education, where emotional cues can influence engagement. However, adding realism also increases complexity. Fine motor control systems, distributed actuation, high-density sensor arrays and AI inference pipelines must operate seamlessly to maintain the illusion of natural behaviour.

This convergence of aesthetics and autonomy introduces new considerations for deployment. Public-facing robots that resemble humans raise questions about transparency, identity disclosure and ethical boundaries. Designers must balance familiarity with clarity — ensuring users understand they are interacting with a machine, even if it appears human-like.

There is also a broader systems engineering question: does increased anthropomorphism meaningfully enhance operational performance, or does it introduce new risk factors without corresponding functional benefit? In industrial and logistics robotics, performance metrics are typically measured in throughput, reliability and safety. In social robotics, success becomes harder to quantify.

As embodied AI platforms continue to advance, the debate is likely to intensify. The technical achievement of producing lifelike motion and expression is significant. Yet long-term adoption will depend not only on mechanical sophistication and AI capability, but also on regulatory frameworks, safety validation and public acceptance.

In that sense, ultra-realistic humanoids are not just a robotics milestone — they are a test of how far society is prepared to integrate machines that increasingly mirror human presence.